Performance prediction

In computer science, performance prediction means to estimate the execution time or other performance factors (such as cache misses) of a program on a given computer. It is being widely used for computer architects to evaluate new computer designs, for compiler writers to explore new optimizations, and also for advanced developers to tune their programs.

There are many approaches to predict program 's performance on computers. They can be roughly divided into three major categories:

- simulation-based prediction

- profile-based prediction

- analytical modeling

Simulation-based prediction

Performance data can be directly obtained from computer simulators, within which each instruction of the target program is actually dynamically executed given a particular input data set. Simulators can predict program's performance very accurately, but takes considerable time to handle large programs. Examples include the PACE and Wisconsin Wind Tunnel simulators as well as the more recent WARPP simulation toolkit which attempts to significantly reduce the time required for parallel system simulation.

Another type of simulators, trace-based simulators do not run every instruction, but run a trace file which store important program events only. It loses some flexibility and accuracy compared to cycle-accurate simulation mentioned above but can be much faster. The generation of traces often consumes considerable amounts of storage space and can severely impact the runtime of applications if large amount of data are recorded during execution.

Profile-based prediction

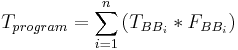

The classic approach of performance prediction treats a program as a set of basic blocks connected by execution path. Thus the execution time of the whole program is the sum of execution time of each basic block multiplied by its execution frequency, as shown in the following formula:

The execution frequencies of basic blocks are generated from a profiler, which is why this method is called profile-based prediction. The execution time of a basic block is usually obtained from a simple instruction scheduler.

Classic profile-based prediction worked well for early single-issue, in-order execution processors, but fails to accurately predict the performance of modern processors. The major reason is that modern processors can issue and execute several instructions at the same time, sometimes out of the original order and cross the boundary of basic blocks.